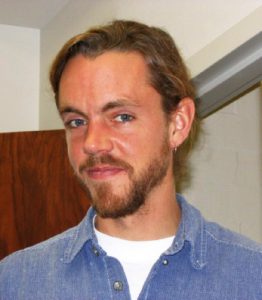

AJ Wortley, who has been with the SCO since the 1990s, will be leaving the office at the end of January, 2018, to begin a new phase of his career in software development at Earthling Interactive in Madison.

AJ Wortley began working for the SCO as a student assistant in 1995, while he pursued a degree in Civil Engineering from UW-Madison. In April 1998, AJ began a 50% appointment in the SCO as an Outreach Specialist. In May 1999, AJ’s position was expanded to full-time through assistance from a grant from the Wisconsin Land Information Board. Other federal grants continued to fund a portion of AJ’s position until 2003, when his position became fully funded through the SCO’s annual budget.

The following are excerpts from an interview with AJ in December, 2017.

Q. You’re from Indiana originally. How did you end up in Madison?

I came to Madison to go to college. In the early nineties, I was looking for a college I could afford on my own and that was far enough away from home, but still close enough that I would be able to return to visit family periodically. I applied to universities all over the Midwest and a few that I couldn’t afford elsewhere, and after visiting others in Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois. I chose Madison. There was something special about Madison that felt different. I came here for engineering. I wasn’t sure what kind – maybe chemical or electrical – but then settled on civil engineering as something more tangible… which which ultimately led me to geographic information systems.

Q. Tell us about those early years. How did you end up at the SCO and what projects did you work on?

As an undergrad in the third year of my engineering degree, I approached my advisor, Professor Scherz, for some career advice. He suggested that, while it was fine to have a job at a pizza joint at night, I should probably be looking for a job to get some experience in my field. He looked down at a flyer for a student position that he was supposed to post it on his bulletin board outside his door and said, “Well, how about this place, the State Cartographer’s Office? They do good things down there.” He couldn’t tell me exactly what those good things were, but I went and applied and got the position that same week, as a student hourly, to begin in January of 1995.

I was hired to digitize third-order vertical control off USGS Topo quads. Ultimately these became part of the data that is now in SurveyControlFinder. Before that, they were distributed in a variety of formats with re-packaged data sheet lookup software on 3-1/2-inch floppy disks and, later, CDs.

I worked on the digitizing project for about 6 months. I also did things like catalog the office’s CDs of data and various other student tasks: updating the aerial photograph catalog (in analog form), the soil mapping guide, and the geodetic control guide. The SCO at the time produced a series of printed guides and students did everything from research to illustration support. I had to do manual phone calling questionnaires for aerial photography catalog updates. There were just a variety of projects we worked on. We did have computers to work on, but we were barely networked together. One person had a computer who had a portion of it shared out to the rest of us under Windows 3.1 but we didn’t actually have a server.

I worked in a room with several other students. Back then the SCO was on the main floor of Science Hall. I think there were six or eight of us in Room 144. I worked alongside Hugh Phillips, who worked on a borrowed SPARC UNIX workstation creating the first z39.50 WISCLINC clearinghouse node for the state. When I came back as a half-time employee, they cleared out the magazine archives in the back of Room 155 and I had the back of that room while the front was magazine storage. Later we cleared out the magazines to make room for graduate students to work with me on our grant-funded projects. This was before the SCO moved to the third floor.

When I was a student hourly the SCO did not yet have a website. I was envious of the fact that a couple of graduate students were hired to create the first SCO website and while I could peer over their shoulder, that was graduate student work. They created the website by converting the SCO’s information that they had on what was called a BBS system. The original website was like a BBS because you had to click down through branches to get to individual detailed pages. Those early days nonetheless sparked my interest in the programming language(s) of the internet and its intersection with my own work.

Q. How did you end up back at the SCO as an employee?

I left the SCO as a student assistant when I graduated in 1997, and sought out some other civil-related experiences, including working in construction for a year. This was also a conscious choice based on the fact that my son Sam was about to be born. In fact I was still working in construction when I came back one day to a house that I no longer lived in, as I had just moved to a new apartment, and found a voicemail on my ex-roommate’s answering machine from Ted Koch saying that the SCO had a half-time position open, and I that I should apply. I took that as one of those signs in life, when someone tells you that you ought to apply for a job, then you do. So I did.

I was hired to focus on metadata education throughout the state in conjunction with the creation of a clearinghouse because we needed metadata documents to feed the clearinghouse. I did workshops, articles for the Mapping Bulletin, individual consulting with counties and state agencies, things like that. We received an FGDC (Federal Geographic Data Committee) grant one year to fill out the other half of my position to do a statewide workshop series, and I gave workshops in university labs throughout the state.

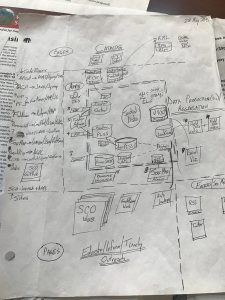

Another FGDC grant was for an interactive map application for the Internet. This was in about 2000 or 2001. We called it OrthoFinder and I worked together with a graduate student Woody Wallace on it. He programmed it in Java because that’s what he knew from his work as a USGS contractor before he came back to work on his master’s degree in Geography. We were the first team in the office to work on interactive mapping using MapServer and open source programming. OrthoFinder ultimately would be retired. It was an interesting idea. It was an extension of the Aerial Photography Catalog to try and show the different orthophoto series throughout the state by spatial footprint, but we re-used the concept of it to hatch ControlFinder, PLSSFinder and later WHAIFinder.

Q. I heard there is a good story about you in a staff meeting at this time.

It was shortly after I started working here, so I didn’t have a whole lot of confidence yet. We had notoriously long staff meetings that would go on for hours and hours because we never took things off the agenda, we just kept adding them. As this particular meeting wore on I got a little antsy, and finally said “If you don’t mind, I need to leave because I’m supposed to get married pretty soon.” Everyone just stopped talking and looked at me. I think I offered to come back afterwards, but Ted Koch suggested it might be a good idea to take the rest of the day off.

Q. You’ve always been a big advocate for open source software. What started that?

I’d say certainly my early collaborations with Paul Gunther and Woody Wallace as well as some of the graduate students that I worked with, but ultimately it was a natural extension of working in technology at the university. Madison has long had a very decentralized information technology landscape, which meant that departments had a lot of freedom to experiment. I have always been a fan of things that you could open up and understand how they worked. That’s part of my engineering background and being able to try to tweak those solutions or change them to do something else that you might want them to do. I was later very much a fan of hybrid solutions, but I learned a lot from some folks who were very adamant about one way of doing things — the open way. That exposure did give me a lot of opportunity to learn things outside the traditional scope like administering Linux servers and building and compiling open source libraries. I’m a big believer that the university encourages employees to use the talents they have to pursue their mission, at times in unique ways. I think other workplaces these days actually are working harder to foster some of that as well, including the private sector which is going a long way, at least in the technology front, to encourage employee experimentation and innovation in a way that they didn’t use to.

Q. How did you get started in application development?

As a result of our FGDC grant applications, we not only had website, but we had a java-based OrthoFinder application. We had created early web map and web feature services, delivering survey control, boundaries and some other kinds of data as test beds. We had a statewide WISCLAND land cover web map service running as a demo. So we were exploring. We knew web services would have some kind of an implication within the geospatial ecosystem. And we were actively exploring how they were created, what they looked like, what they were useful for. It was mostly in a peer-to-peer role with the students who were funded under the same grants that I helped write with Ted Koch. Then when Bob Gurda retired from the office, Brenda Hemstead and I divided up a fair number of his duties along with Ted. That’s when my role supervising students was really strengthened and pursuing map application development with the talented students was a no-brainer.

Q. What projects or initiatives that you worked on for the SCO are you most proud of?

The top one would simply have to be both the diversity and quality of students that I’ve worked with over the years and what they’ve gone on to do. I had an advantage over anyone who might have supervised them in the past in that I was a student assistant in this office, and then had the opportunity to collaborate very directly with one to two graduate students, before moving on to supervise the lab of students. I took a tact that kept me very connected to the students, not only while they were working here but after they left. And that probably gives me the most pride — that we were able as an office and as a collective of staff to give our students the opportunity to demonstrate what their education and talents could produce.

The top one would simply have to be both the diversity and quality of students that I’ve worked with over the years and what they’ve gone on to do. I had an advantage over anyone who might have supervised them in the past in that I was a student assistant in this office, and then had the opportunity to collaborate very directly with one to two graduate students, before moving on to supervise the lab of students. I took a tact that kept me very connected to the students, not only while they were working here but after they left. And that probably gives me the most pride — that we were able as an office and as a collective of staff to give our students the opportunity to demonstrate what their education and talents could produce.

I’m super appreciative of the opportunity that I’ve had here. I’ve had a relatively unparalleled opportunity to explore new ideas and new technologies, and constantly have had to keep pace with the student workforce that is forever changing in its incoming abilities and understanding. I went from having to teach them how the web works to having them teach me what they already knew so we knew where to start advancing our knowledge together.

Another source of pride is that in more recent years we have developed productive relationships with the Robinson Map Library and the Cartography Lab, specifically Jaime Martindale and Tanya Buckingham. The SCO was always a big supporter of the Map Library, particularly when Jamie Martindale arrived, but I think some of our recent collaborations have helped to solidify the relationship and make it more tangible. Through shared applications and workflows we’ve been able to do bigger things and in a more informed way than we would have just within the office alone.

A few last thoughts…

I’d like to particularly thank the staff of the State Cartographer’s Office – Howard, Jim, Brenda, Codie and David. In a small office you end up meshing more than duties and I appreciate what we were able to accomplish collectively.

Lastly, I’m proud to have been part of and helped found the weekly social networking group “WearyMappers” which started back in 2004 or so. This group reflects a wide range of backgrounds including university, federal, state and local governments as well as private sector and non-profit folks. Discussions often are centered around GIS, Internet mapping, open source and democratization of information – mapped and otherwise which is a great opportunity for students to network professionally. Mappers may often be found Tuesday evenings at the Weary Traveler Free House in Madison.

Q. Tell us about your time as President of WLIA.

I had served on the board of directors for four years, quite a few committees, and had the opportunity to work with a variety of professionals around the state. A former board member approached me and asked if I would run, and told me that someone else had also been nominated. WLIA usually only runs one candidate but I suggested that I’d like to see the association actually run two people for president. And to my knowledge, that’s the only year they ever did. John Schwichtenberg and I both ran for president that year. What I did not anticipate is that I would have to organize the annual conference at the Monona Terrace Convention Center in Madison, which is historically too expensive for our association, in February of 2011, which would be the year of thousands of people were protesting around the Capitol during the conference. It was brutal, with lunch-time seminars sometimes seeing only fifty percent attendance because people were going out to see what was going on in their state.

I had served on the board of directors for four years, quite a few committees, and had the opportunity to work with a variety of professionals around the state. A former board member approached me and asked if I would run, and told me that someone else had also been nominated. WLIA usually only runs one candidate but I suggested that I’d like to see the association actually run two people for president. And to my knowledge, that’s the only year they ever did. John Schwichtenberg and I both ran for president that year. What I did not anticipate is that I would have to organize the annual conference at the Monona Terrace Convention Center in Madison, which is historically too expensive for our association, in February of 2011, which would be the year of thousands of people were protesting around the Capitol during the conference. It was brutal, with lunch-time seminars sometimes seeing only fifty percent attendance because people were going out to see what was going on in their state.

And then the next year, while President or soon after, the Register of Deeds legislation was proposed to preserve the five dollar redaction fee. During my own time I worked with the WLIA Board and legislative committee to advocate for keeping that fee and redirecting it toward increasing the WLIP base budget. That’s ultimately what happened with the efforts of a lot of folks and the Wisconsin Counties’ Association. In my mind it’s one of the best things that’s happened to the WLIP and WLIA in the last decade.

Q. What are your thoughts on the state of the Wisconsin geospatial community?

Early on as I was becoming more educated about the land information program (WLIP) a big influence on me was Jerry Sullivan. He was a fountain of information who, no matter what question I had, would give me a bibliography of related events and people. I quickly learned of the rich history and aspirations of the program.

In the early years, advocacy sometimes took a very public and occasionally ugly type of form, and I don’t think that some of those things, if revisited in hindsight, were overly productive. Some of them probably left the association and the program in limbo for a couple of years longer than necessary, in order to work through old feelings. Later I think it was a combination of angst over spending authority within the program and later budget lapses within that same fund that led to bad feelings.

I have long struggled with the notion when the WLIA was led entirely by county leadership whether or not they were entirely advocating for a full state benefit. There were many, many statements about the WLIP being for counties only, and it was very evident to me when those kinds of statements were thrown around, that they meant people employed by counties, period. That would lead to another smaller but important emphasis that I tried to bring when I was president of WLIA, which was the inclusion of municipalities. And I worked hard to have some key conversations with people I thought were leaders in trying to pull Wisconsin’s municipalities together within the geospatial community. Folks like Adam Dorn.

Q. Is there something uniquely adversarial about the Wisconsin geospatial community and the Wisconsin psyche in general? Or just something that was specific to that particular group of people at that time?

Not being originally a Wisconsinite but having lived here a long time, I am still trying to figure out in that context if that was part of the Wisconsin tradition of debate in public governance or if the geospatial community in particular was just particularly cranky and adversarial at times. Some would argue it was absolutely necessary.

I think there are some roots of it in Wisconsin politics, from Fighting Bob LaFollette onward. Even the sifting and winnowing for the truth in the university’s mission is hardly a painless process. I think politics pervades Wisconsin culture from the coffee shop to the pub after work. And I think there can be — with good people in good temperaments — good outcomes from that. I think it’s when we don’t have our own egos in check and try to talk louder than somebody else, or when we don’t listen to the other side, that we don’t tend to make as much progress. So I’m actually more encouraged now by the relationship between the land information community and the executive and legislative branch of state government than I was back then. We’re not as loud now and as pep-rally-like, and our town hall meetings certainly don’t get to the heart of some of the real issues at hand, but we are more productive in our communicative relationship with the administration and legislative leaders that have particular human touch concerns. And from that perspective, somehow I think the community has matured.

Within the community, I think our capability and our pride can also be our downfall. I hope Wisconsin continues to look at examples from other states. I think we have a long proud tradition, but we’ve not always been good at leapfrogging ahead by acknowledging the other states who’ve done some of the work whereby we don’t need to recreate our own ideas here every time.

Q. How do you see the community going forward? What still remains to be done?

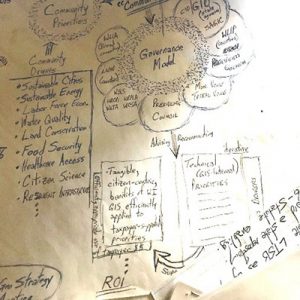

I think one of the most important transitions that’s happening and that I think will continue to help, is for the geospatial community to acknowledge itself as not being so overly special but rather widely applicable. I’m very much looking forward to future opportunities where geospatial is a unique component and a service working within a much larger IT environment in the world of software solutions. But it’s by no means the single most special one, and sometimes to isolate yourself as such invites not only deeper inspection but the opportunity to get eliminated as a single line item. I think that for the WLIA and WLIP, and in general the geospatial community, involvement through continued advocacy around things like deer habitat protection, monitoring of housing prices in a post-recession era and next generation N-G-911 are examples where we can apply geospatial technology to issues that tangibly and visibly matter to the citizenry of Wisconsin. I think that is probably one of our biggest advantages if we can continue to do that going forward. It’s hard to say if there will always be a need for something called the Land Information Association — or if those folks who work within the different application domain areas naturally come together and it’s just a technology that pervades those areas — but I see that it still has an opportunity to stay relevant and meaningful. But not just for the sake of a map because that’s not compelling by itself anymore.

Q. What do you think the SCO will be doing in 10 years?

One of the biggest challenges has been that this office has few analogs across the country — and that’s both a blessing and a curse. One side of me would like to say that the office will be wherever it wants to be in ten years, wherever it seeks and strives to be, in so much as we’ve always had to be proactive in order to continue to exist. Because, with few analogs, it’s easy to say, well why do we need one when no one else has one? At the same time I think that there’s a real opportunity for using this office as a way to reset the model that I feel like is a little broken right now for public academic cooperation and collaboration. The office has experienced over time historically and even up to present — this notion that the university can’t do real work or work that has a sustained public impact. I don’t believe that’s true and believe something quite the opposite should be promulgated here, with the Wisconsin Idea still in place. I think that this state more than many others has an opportunity, in the same way that the agricultural extension worked a hundred years ago, to create professional opportunities for university students while pursuing collaborative goals the state would like to accomplish given a smaller state budget and a smaller state workforce. So I think the SCO can help set an example like that within the geospatial community, by working with the kinds of entities that we do, including state and local government as well as the private and non-profit sectors. I think the public sector is going to have to get used to getting smaller for a while and that there’s going to be plenty of work to do for those that are looking for it.

One of the biggest challenges has been that this office has few analogs across the country — and that’s both a blessing and a curse. One side of me would like to say that the office will be wherever it wants to be in ten years, wherever it seeks and strives to be, in so much as we’ve always had to be proactive in order to continue to exist. Because, with few analogs, it’s easy to say, well why do we need one when no one else has one? At the same time I think that there’s a real opportunity for using this office as a way to reset the model that I feel like is a little broken right now for public academic cooperation and collaboration. The office has experienced over time historically and even up to present — this notion that the university can’t do real work or work that has a sustained public impact. I don’t believe that’s true and believe something quite the opposite should be promulgated here, with the Wisconsin Idea still in place. I think that this state more than many others has an opportunity, in the same way that the agricultural extension worked a hundred years ago, to create professional opportunities for university students while pursuing collaborative goals the state would like to accomplish given a smaller state budget and a smaller state workforce. So I think the SCO can help set an example like that within the geospatial community, by working with the kinds of entities that we do, including state and local government as well as the private and non-profit sectors. I think the public sector is going to have to get used to getting smaller for a while and that there’s going to be plenty of work to do for those that are looking for it.

Q. So what about you? What lies in your future?

I still feel like an engineer. I like to build things that involve both technology and people. So I’m looking forward to an expanding role in project and product management, in software development, and technology development. I think that suits me right now and I have a lot to learn frankly. Part of my reasoning for leaving the university also relates to students. I have really enjoyed mentoring students and finding non- traditional geographers and watching them become programmers, but I have started to feel like I was losing traction on what that meant in this day and age and I’m not sure that I found a place at the university that gave me direct access to the emerging patterns in software development architecture and distributed cloud-based application programming development. And so I’m going somewhere else in order to keep learning and get back on the front edge of where it’s all going to be.

I wouldn’t rule out ever returning to the public sector. Wisconsin is where I call home and the place I care about first now, and I do think that there are places in the public sector for people who are passionate about this state and its future and the citizens here. I just think it’s my time to go develop some other skills and learn a little more about myself before I reconsider that question.

GOOD LUCK AJ, FROM ALL OF US!!