Science Hall occupants may have noticed activity around the Grand Canyon relief model on the second floor of the building over the summer of 2019. This activity was actually a painstaking effort to clean, stabilize, and repair the model using state-of-the-art materials and conservation techniques.

The conservation effort was initiated by the editors of the History of Cartography Project, who plan to use a photograph of the relief model in an entry and on the cover of Volume 5, the final volume to be published in the series. The conservation of the model was funded by the UW-Madison Geography Department and a donation from Rosalind Woodward, wife of the late David Woodward who co-founded the History of Cartography Project and served as its editor until his death in 2004.

Lindsey Buscher, senior research editor for the History of Cartography Project, explains,

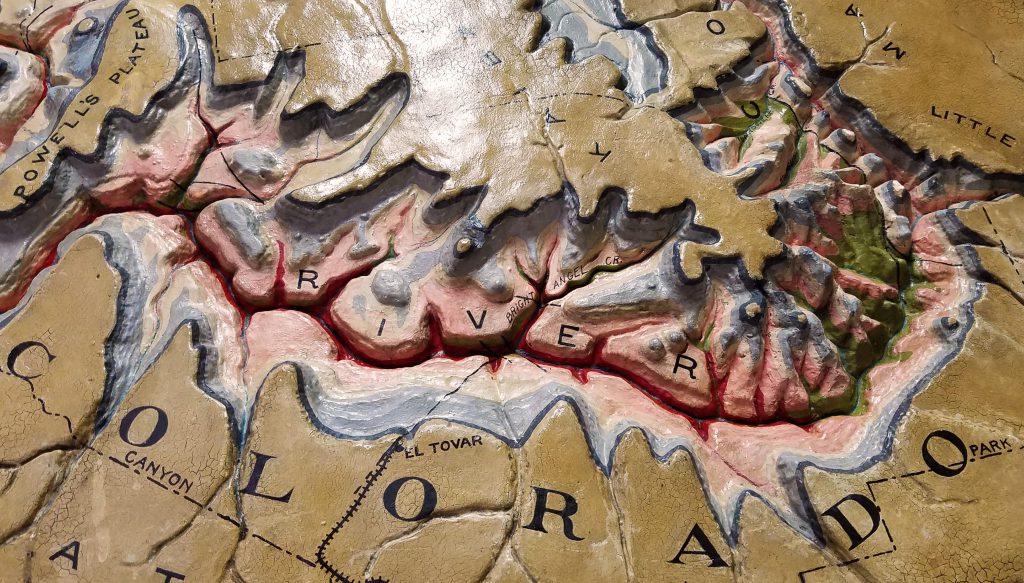

“The connections between this particular relief model, the history of its presence in Science Hall, and the History of Cartography Project (which has been located in Science Hall since its inception in 1981) were fascinating to piece together. When I realized one day while filling up my water bottle on the second floor that this Grand Canyon model appeared at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia—which just so happened to be mentioned in a Volume 5 entry I had been working on that day about cartography in the public sphere—I knew it would be important to have a photo of this beautiful artifact in the book.”

The Grand Canyon relief model is Science Hall’s oldest model. In fact, it is older than Science Hall itself. According to Melanie Schleeter McCalmont’s book “A Wilderness of Rocks: The Impact of Relief Models on Data Science,” the model is the oldest commercial relief map in the United States. It was created by Edwin Howell in 1875 based on information available at the time, including John Wesley Powell’s Grand Canyon expeditions.

As McCalmont’s book documents, there are many other relief models from this era on display at locations around the state including Science Hall, the UW-Madison Geology Museum, UW-Whitewater, and UW-Milwaukee. The Grand Canyon relief model was most likely left in Science Hall in about 1980, when the Geology Museum moved out of the building.

chipping and discoloration (photo by Lindsey Buscher)

Complicating the History of Cartography’s plan to use a photo of the model for Volume 5 was the condition of the model itself. Nearly one hundred and fifty years of exposure to the environment had taken a toll. The model was covered in dust, the plaster had several good-sized cracks in it, and the paint was chipped and flaking in many spots. Paint discoloration was also evident from exposure to sunlight over the decades.

As Buscher notes,

“Eventually it was decided that the damage was too extensive to be able to use a good enough photo of it in its current state, so we teamed up with the Geography Department and the State Cartographer’s Office to hire a professional conservator.”

Conservation was done by Craig Deller, who is the materials conservator at the Wisconsin Historical Society and Senior Conservator of the Deller Conservation Group in Madison. Deller was trained at the Smithsonian Institution’s Conservation Analytical Laboratory and was elected a Fellow of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works in 2015.

(photo by Lindsey Buscher)

Deller was assisted by Sarah Stankey, who completed her Master of Fine Arts degree at UW-Madison in 2019 and now works as a preparator/photographer at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art. She performed the tedious and delicate work of painting the areas that had been stabilized and filled in where the more extensive damage had occurred. Stankey also took photos of the progress throughout the process as well as the finished product.

The conservation approach adopted for the Grand Canyon relief model included:

- Scanning with a metal detector to determine whether a woven metal substrate exists (negative)

- Cleaning the model and frame with aqueous-based artificial saliva

- Solvent testing with acetone (negative), ethanol (positive), and mineral spirits (negative)

- Stabilization of edges of paint loss and bare plaster areas with a finely dispersed, aqueous dispersion of an acrylic copolymer

- Filling areas of plaster loss with a cellulose-based fill material

- Sealing of the entire surface with a solution of B-72, an acrylic resin soluble in acetone, ethanol, and xylene

- In-painting using Maimeri Restoration Colors and Gamblin Conservation Colors

There were large areas of previous over-paint that were left in place, along with numerous previous touch-ups presumably made when the model was updated over the years.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the conservation lies in the fact that the in-painting was done on top of the B-72 sealant. The in-painting can be removed using mineral spirits without affecting the sealant coat, and the sealant coat can be removed using acetone, which does not interact with the finish of the original relief model. This approach means that the repairs made to the model are non-destructive and can be removed.

The treatment report for the relief model can be found here for readers who want more detail on the techniques used.

“The editorial team is very pleased with the results and excited to use the photos in Volume 5,” said Buscher.

Please contact me (Howard Veregin, veregin@wisc.edu) or the History of Cartography Project (Lindsey Buscher, lbuscher@wisc.edu) if you have questions.

(photos by Lindsey Buscher and Sarah Stankey).

Click on the image for a larger, interactive version.

(Juxtapose.js is by the Northwestern University Knight Lab)