Have you ever wanted to travel back in time? Walk through a landscape that no longer exists? Visit the small town that grew into the big city? Well, this is now possible — in a manner of speaking — using your smartphone and a special type of file called a geospatial PDF.

A geospatial PDF is a file format used to store and display maps. Geospatial PDFs extend the common Portable Document Format (PDF) specification to allow file content to be “georeferenced” — or positioned correctly relative to other features on the earth. This means that a geospatial PDF can be displayed on your smartphone with your location and a GPS track drawn on top. For this reason geospatial PDFs are popular for outdoor recreational activities when cell phone service is poor. For example, hikers and ATVers can track their locations and navigate effectively using geospatial PDFs showing recreational trails, even without access to Google or Apple maps.

You can read more about geospatial PDFs in this SCO Technical Paper.

Time travel

Time travel on your smartphone is made possible by the availability of historic maps that have been converted into geospatial PDF format. Probably the largest collection of these maps is from the US Geological Survey (USGS), which has made its scanned historic topographic maps freely available online. There are hundreds of maps covering Wisconsin, from as early as the 1880s, at a variety of map scales. The most recent USGS “US Topos” from 2018 are also available, along with the classic 7-1/2 minute “quads” that many users will be familiar with.

There are several ways to access the USGS historic maps, but perhaps the easiest is the online topoView app that allows you to search for all maps by clicking any spot on the base map, preview these maps on your computer screen, and download maps in geospatial PDF format. (Other formats are also available.)

Side Note: The USGS historic maps were georeferenced using software developed in the UW-Madison Geography Department by Emeritus Professor Jim Burt. Jaime Martindale, who directs Geography’s Robinson Map Library, served as metadata subject-matter expert during the pilot stages of the project, while Geography students scanned more than 15,000 of the topographic maps. See this SCO news article for more information.

To use geospatial PDFs on your smartphone, you also need a map viewing app. I used Avenza Maps, which is available for free. (Other apps are available, and my reference to the Avenza product should not be taken as an endorsement.)

Avenza has many maps available on its store, including some historic USGS maps. To access a specific USGS map that is not on the Avenza store, you can download the map as a geospatial PDF to your smartphone using the USGS topoView app, and then save the PDF to a folder location on your phone. When you import a map into Avenza, you will be able to specify the file location. You can also import the map from a cloud account like Dropbox or iTunes, or just specify the map URL.

Dane County

With this simple setup I recently did some time travel in Dane County using the oldest set of USGS maps I could find. I needed nine maps to cover the entire county. All but two maps (Columbus and New Glarus) were published before 1910, with the oldest map (Evansville) being from 1889. Many of these maps came out in later editions with changes made to map content. For example, the 1890 Stoughton map has editions published in 1896, 1908, 1910, 1934 and 1950.

My goal was to travel back in time and visit some of the communities shown on these maps, to see what they look like today. Some of these places, like Wauankee and Sun Prairie, have grown into large incorporated cities. Other mapped communities, like Paoli and Roxbury, are known “unincorporated places” identified with an unincorporated place sign.

Town of Montrose, Dane County

My interest is with a third class of communities: places shown on the maps that you would probably not even notice if you passed through them. It’s not always fair to say that these communities have disappeared, since there may still be homes present and people who live in them. But often these homes are scattered, and there are no businesses in the area, no signs proclaiming the place name, and no change in the speed limit to warn drivers to be on the lookout for residents crossing the road. If you did not have the historic map as evidence, you would probably never know that a named community with a post office, a school and a corner store existed at the location a hundred or more years ago.

I visited about a dozen of these communities, mostly in the southwest and northeast parts of Dane county. In the remainder of this article I’ll share what I found at four of these locations. I did not include any places within the current boundaries of Madison and Monona, but these are plentiful, and would make an interesting field trip. The locations I visited were primarily rural.

Notes

It’s often possible to use the historic USGS map to navigate to the location you are looking for. I found that in many rural locations, the roads on the historic maps were a good match to today’s road network. All I needed to do was load the map into the Avenza app, turn on GPS tracking, and then navigate by giving verbal instructions to my travel companion, who did the driving. This approach may not work in urban areas where the road network has been more heavily altered.

I used Frederic G. Cassidy’s Dane County Place-Names — originally published in 1947 and updated in 1968 — to find more information on the names and history of the places I visited.

Side Note: Jamaican-born Cassidy was an English Professor at UW-Madison and served as Chief Editor of the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) project. DARE was housed at UW-Madison until the completion of the final volume in 2013. The goal of DARE is to document “words, phrases, and pronunciations that vary from one place to another” to demonstrate that “there are many thousands of differences that characterize the dialect regions of the U.S.”

I used the Statewide Parcel Map app to help identify the current property classes (residential, commercial, etc.) of the parcels in the communities I visited. This approach helped clarify whether remaining buildings were still residential. The Statewide Parcel Map is produced annually by the State Cartographer’s Office in conjunction with the Department of Administration and the state’s seventy-two county Land Information Offices.

I used GNIS (Geographic Names Information System) to find out whether any of the communities I visited still had an official name. GNIS is the repository of US toponyms (geographic feature names) maintained by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names. Online mapping apps often use GNIS to label map features, as does the USGS in its current series of topographic maps. However, not all GNIS data is of equal quality, and users should be cautious especially about names for cultural features since some of these are quite out-of-date.

Lakeview

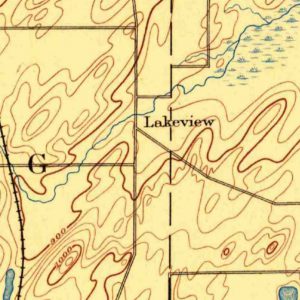

Lakeview is labelled on the 1894 Evansville topo map at a crossroads several miles north of Oregon.

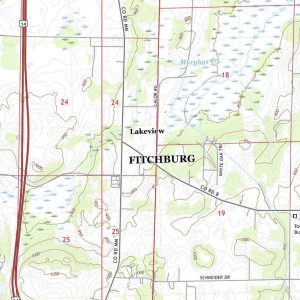

Today this is the intersection of County Highways B and MM within the corporate limits of the City of Fitchburg, which encompasses much of the former Town of Fitchburg. A half-dozen homes are located at this highway intersection, most of them along Highway MM south of Murphys Creek. The Statewide Parcel Map shows six parcels in the area classified as residential and having an improved value greater than zero (indicating the presence of a building). The intersection is a busy one today in part because of an active sand and gravel operation a half a mile south.

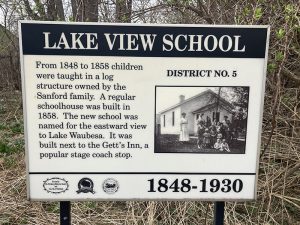

There’s a small plaque on the west side of County MM commemorating Lake View School, which stood here until 1930. The plaque also refers to Gett’s Inn, a stage coach stop along the road. The Inn no longer exists.

In Cassidy’s Dane County Place-Names Lakeview is described as a “corner” community or “small crossroads settlement” in section 24 of the Town of Fitchburg. According to Cassidy it was named for the Post Office, which was called Lake View PO when it was established on July 1, 1848. The name was changed to Lakeview PO in 1895 before it was finally discontinued in 1901.

The name Lakeview apparently refers to the fact that Lake Waubesa was visible from this location. This does not seem to be the case today, probably due to regrowth of trees on the cleared pasture and cropland that predominated in the area in the past.

With the exception of the small school plaque, there’s nothing to alert the passing driver (or brave cyclist) to the presence of Lakeview. Lakeview was probably never very large, but presumably was more noticeable when it still had its school, inn and post office. Today there isn’t even a reduced speed limit within Lakeview and vehicles pass through at the posted limit of 50 mph.

Like some other unincorporated places, the Lakeview label appears on Google maps. This could be because it is listed in GNIS (Geographic Names Information System) as a “populated place.”

Story

In contrast to Lakeview, the community of Story has essentially disappeared.

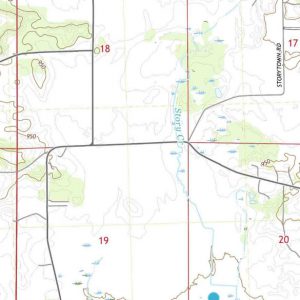

This community appears on the Evansville topo map from 1906. Story was located in Sections 17, 18 and 19 of the Town of Oregon. Today, Story’s main street is a half-mile section of County Highway A, between the intersection with Highway D to the west, and the intersection with Storytown Road to the east.

The 1906 map shows a handful of buildings scattered along this stretch of road, along with a school just to the east of the intersection of Highway A and Storytown Road. As the Statewide Parcel Map confirms, Story is now predominantly an area of agriculture and forest.

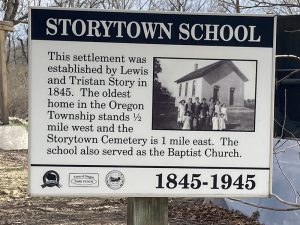

There are a few residential parcels along Storytown Road, one of which is at the location of the old schoolhouse. A plaque at this location shows a photo of Storytown School, which apparently also served as the local Baptist Church.

The plaque dates the school to 1845, which is also the date of the settlement itself. It refers to Lewis and Tristan Story, the original settlers, from whom Story (or Storytown) takes its name.

Other residential parcels today are located along Highway A east of the intersection with Storytown Road, close to Storytown Cemetery but this seems to be beyond the extent of Story if we can trust the 1906 map. (And recognizing, of course, that unincorporated communities by definition do not have boundaries.)

According to Cassidy’s book, Story is the more modern name of the “corner community” originally called Storytown. The community was named after the Story family who settled in the area in the 1840s, as we learned from the school plaque. A post office existed from 1890 to 1903.

The original settlement was close to the head of Story Creek, which crosses Highway A just to the west of the old schoolhouse location. Curiously, the first USGS map to show Story is from 1906; the community is absent from earlier maps from the 1890s, despite the fact that Story was apparently settled by this time. Without earlier maps or additional historical evidence, we can’t really tell what the extent of Story was in its earliest days, or what sorts of buildings it may have contained.

GNIS also has a record for Story as a “locale” (unlike Lakeview, which is classified as a “populated place”). It does not seem to appear on Google or Apple maps.

There’s not a lot to alert passers-by to the fact that a community once existed here, except for the plaque and the cemetery, both of which refer to Storytown.

Door Creek (Deer Creek)

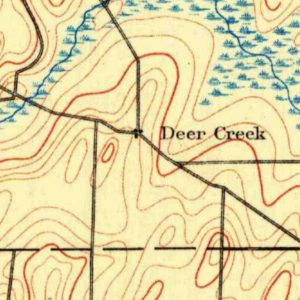

Deer Creek first appears on the 1890 Sun Prairie map. On the 1896 map the name has been changed to Door Creek.

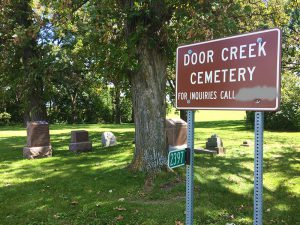

According to Cassidy, Door Creek, a small crossroads community, was first known as Buckeye. The name Deer Creek, as shown on earlier maps, is reportedly an error. Door Creek was named after its post office, established in 1847 and permanently disestablished in 1902. The post office, in turn, appears to have been named for the creek of the same name. The community is classified as a populated place in GNIS.

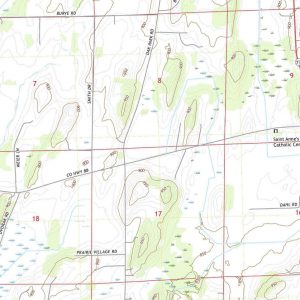

Based on the map evidence, the actual location of the community of Door Creek is somewhat ambiguous. The historic map shows the community at the intersection of what is now US Highway 12/18 and County Highway N.

This is also the location shown in GNIS, which explains its location on the 2018 USGS map (and most likely Google Maps too). This location is close to the center of Section 33 of the Town of Cottage Grove. However, according to Cassidy, sometime before 1890 Door Creek was moved east to the line between Sections 33 and 34, due to a road realignment. This location is approximately where North Star Road crosses Highway 12/18, a location close to Door Creek Cemetery and where there are a number of parcels currently classified as residential. So, is this the actual location of Door Creek? There are no signs for Door Creek in the vicinity, so the only way to answer this question might be to ask the inhabitants of those residential parcels.

Meanwhile the mapped location of Door Creek – the location we see on both historic and modern maps – is nothing but a highway interchange. If there ever were homes here they are long gone.

Adsit

Adsit appears on the 1896 Sun Prairie map.

The 1905 map shows the location with the name Oak Grove. Adsit/Oak Grove is a bit north of the present intersection of County Highway BB and Oak Park Rd., on the south edge of Section 8 in the Town of Deerfield.

According to Cassidy, Adsit is named for Stephen H. Adsit and his family, who settled in Section 5, a mile to the north, in the 1840s. The Adsit post office, established in 1882 in Section 5, was moved to the south edge of Section 8 sometime before 1886, before being disestablished in 1899. Thus the mapped location of Adsit on the 1896 map is probably the location of the old Adsit Post Office.

Cassidy also notes that the name Oak Grove has only ever been used on the 1905 USGS map. (Actually it also shows up on the 1907 USGS map, including the 1949 edition of the 1907 map.)

Today there are a few homes along the west side of Oak Park Road north of Highway BB, but the area is largely classed as agricultural. The navigation is also a little trickier, since the 1896 Sun Prairie map is not perfectly georeferenced, or perhaps roads have been realigned or the original 1890s survey was imperfect.

Further north on Oak Park Rd., in Section 5, you can find a memorial to the Adsit family.

There’s nothing to alert anyone passing by on County BB that Adsit ever existed. No signs or old buildings. There’s no label on Google maps either. Anyone driving north on Oak Park Road might notice the Adsit memorial, but there’s nothing there to connect this memorial to a community that once existed. It has all disappeared.

Back to the Future

I’m interested in small rural communities, so I enjoyed my time travel experiment quite a bit. It’s fascinating to see just how temporary rural communities can be in the face of rural depopulation and socio-economic change. And while it didn’t happen on this trip, it’s often the case that these “forgotten” rural communities contain more indelible monuments to the past, like massive stone or brick churches, testifying to the intent of settlers to make these locations permanent rather than transitory.

Town of Christiana,

Dane County

Historic maps of course contain many other features than just communities, all of which can be explored in the manner I have described. Likewise there are other sources of historic maps that could be used, although in some cases the maps are not in geospatial PDF format, so they would need to be converted first. This would require some skills in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) but it could be done. Some examples:

- Sanborn maps of major Wisconsin cities going back to the late 19th century. Georeferenced and available from the Wisconsin Historical Society. These are very detailed fire-insurance maps for urban areas.

- Historic air photos. A statewide 1930s-era set of air photos is available on the WHAIFinder app. The photos are not georeferenced but they can be used when you get back from your field trip to do a little extra sleuthing. Individual images can be downloaded and converted to geospatial PDF format if you have the skills and software.

- Bordner or Wisconsin Land Economic Inventory maps. A statewide set of scanned maps is available online from UW Digital Collections. The Bordner survey is a detailed section-by-section land use survey of most of the state conducted mainly in the 1930s. The Digital Collections scans are not georeferenced, but there is also downloadable GIS data on the Coastal Bordner Explorer app that can be rendered into geospatial PDFs.

Have fun time traveling and make sure you have enough Plutonium to get home!