Last week we started a tour of “cartographic phantoms” in rural Dane County – places that appear on maps but have a) essentially disappeared or b) never existed as communities in the first place. If you have not read Part 1 of the tour, please start there.

The goal of the tour is to draw your attention to the dissonance between what exists physically and what exists cartographically, with specific reference to rural places in Wisconsin.

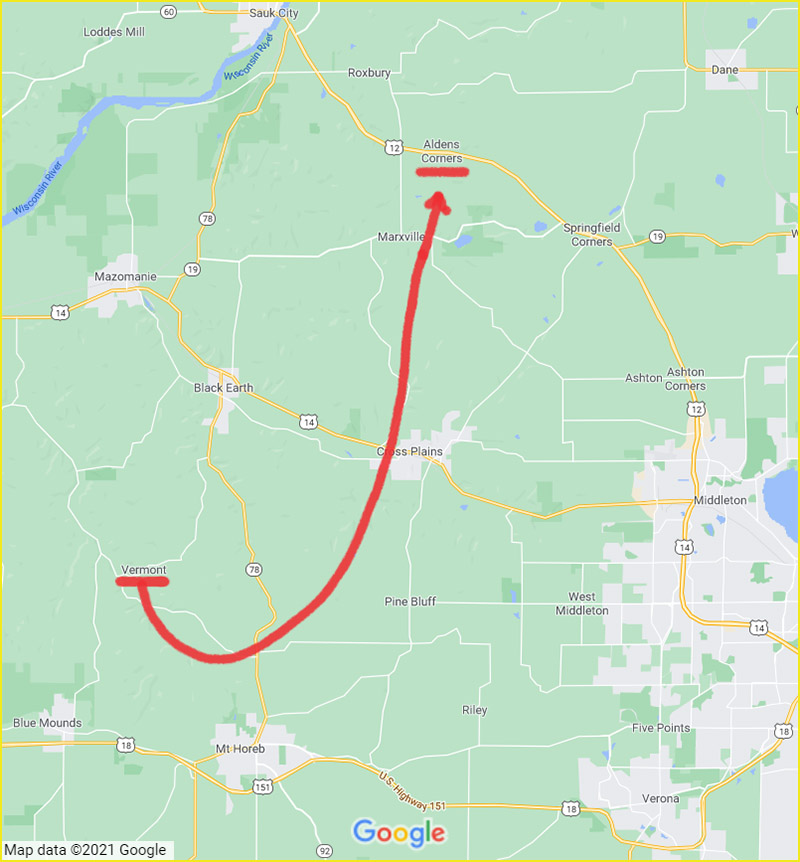

The second part of the tour will take us to the western half of Dane County.

Five Points

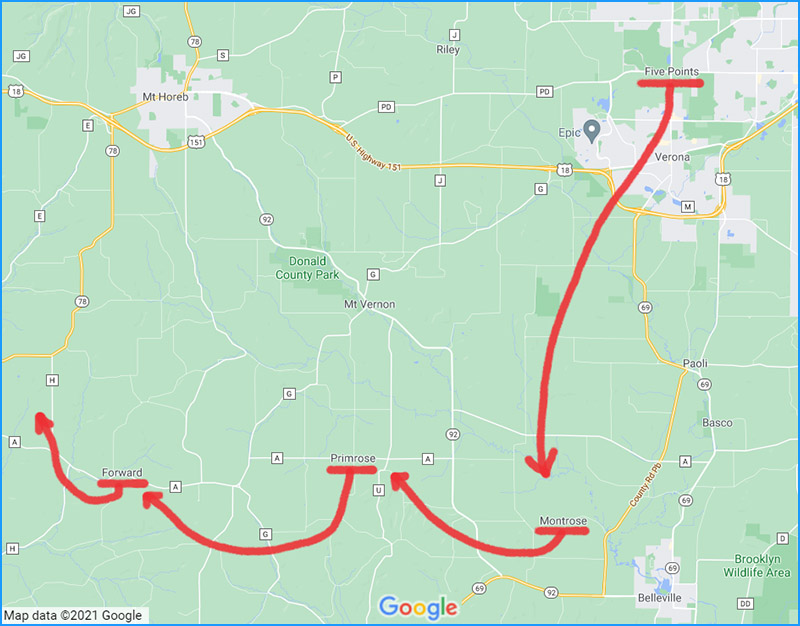

Our first stop takes us just north of Verona, to Five Points, which appears on Google Maps at the junction of North Main Street and McKee Road. Five Points straddles the boundaries of the City of Madison, the City of Verona and the Town of Verona. (Fig. 22)

Today, this road junction is surrounded by a golf course, an electrical substation, an agricultural field and a large residential parcel with several buildings on it. (Fig. 23)

Until recently (sometime between 2017 and 2020) Raymond Road extended to the intersection of Main and McKee (hence the name Five Points presumably) but it has since been truncated. The roads in the area have been widened considerably to accommodate traffic.

The name Five Points was not found on any of our historic Dane County maps and atlases going back to the mid-1800s. Nor does it appear on the WLEI map from 1939. There is no indication that a cluster of homes or businesses existed at this location. On many of these maps, only a single isolated building appears at the road junction, nestled between what is now North Main Street and Raymond Road. (Fig. 24)

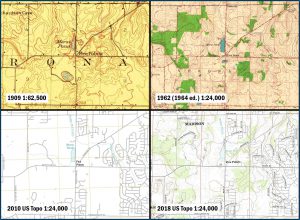

In contrast, US Geological Survey topographic maps display Five Points prominently, starting in the early 1900s. The name continues to appear through the decades on USGS maps of various scales, including all editions of the US Topo Map. (Fig. 25)

Despite the prominent label, there is no indication of a community here on these maps. The only building consistently shown is the one mentioned in the preceding paragraph.

This building seems to still be in existence, the only vestige of the past that remains at this busy intersection. (Fig. 26)

Cassidy agrees that Five Points does not refer to a community, stating that the name Five Points is “descriptive” (p. 58).

Conclusion: It doesn’t seem like Five Points was ever a community, although it may have been used (and perhaps still is) as a geographic reference point by people in the area. Five Points continues to appear on USGS maps to the present day, as well as on Google Maps. Why the connection between USGS and Google? We’ll investigate that briefly after a few more stops on the tour.

Montrose

Next stop: Montrose. On Google Maps, Montrose is at the junction of Montrose Road and Feller Drive, a few miles northwest of Belleville, in the Town of Montrose. It’s in the northwest quarter-section of section 29, Township 5N, Range 8E. (Fig. 22)

Today the junction is surrounded by large parcels of agricultural, forested and undeveloped land. Two residential parcels exist on the north side of Montrose Road, which seem to correspond to the locations (and probably the actual buildings) of the old school and church. There are no services or business present. (Fig. 27)

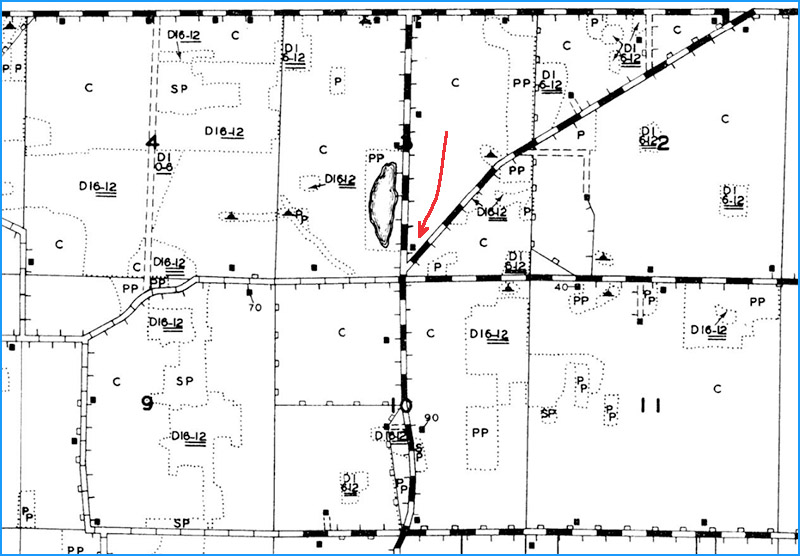

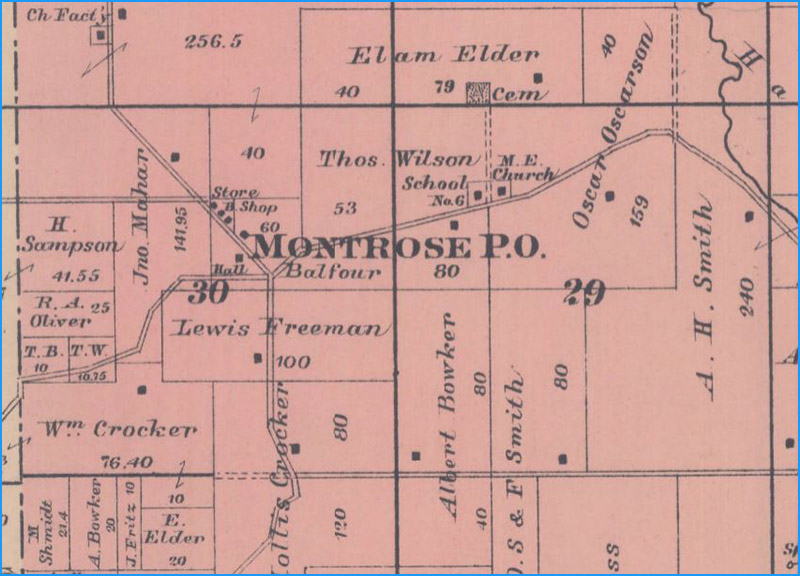

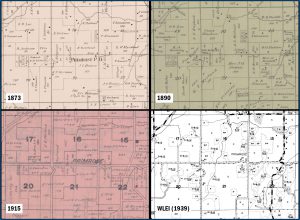

Montrose, like Door Creek, has moved around on maps. Montrose P.O. appears on maps from the late 1800s about a mile west of the school location, in section 30, along with a store, a “B. Shop” (blacksmith?), a hall (the Town Hall perhaps?) and other buildings. (Fig. 28)

Montrose P.O. stays at this location on maps through 1911, at which point the P.O. disappears, indicating that the post office has been closed. This occurred in 1900 according to Cassidy (p. 113).

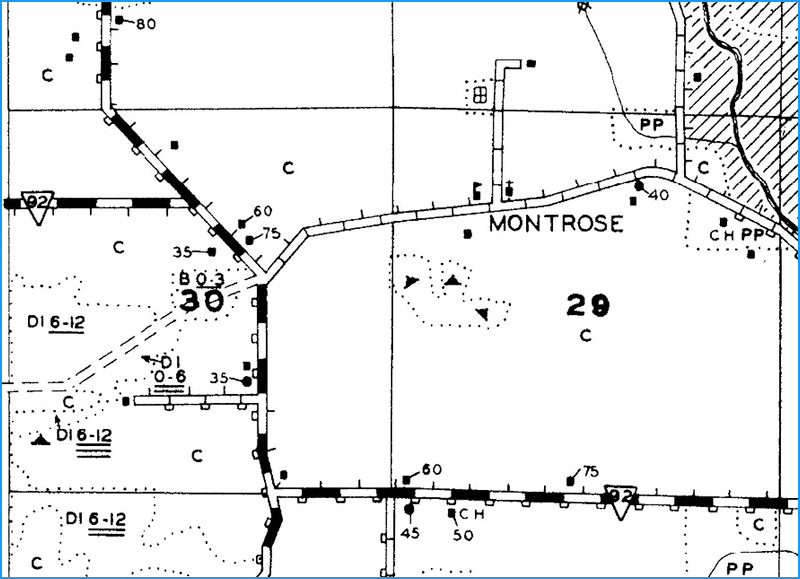

At this point the Montrose map label shifts to the school location a mile to the east, where it stays (roughly) through the 1930s, including on the WLEI map. (Fig. 29)

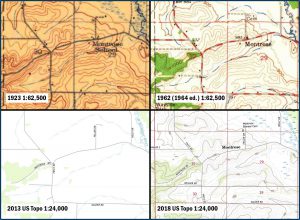

Montrose School appears on the earliest USGS map (1923) but the place name Montrose does not make an appearance until the 1958 1:250,000-scale map, where it sits at the school location. The name continues to appear at this location on various USGS maps over the decades, including the 1960s-era 1:24,000-scale and 1:62,500-scale maps, and all editions of the US Topo maps except 2013. (Fig. 30)

According to Cassidy, the Montrose Post Office was about a mile west of the school location, which agrees with the map evidence. Once the post office was closed, the label for Montrose was moved east close to the school (and church), where it has stayed ever since.

Conclusion: The community at this location is tiny and decidedly off the beaten path, so do not expect to find any services. However, the old school and church are still apparently standing and there’s a cemetery a half-mile north on Feller Drive if you like that sort of thing. There’s not much still standing a mile west, either, where the post office used to be, although there are a few buildings here from the early history of Montrose.

Primrose

Primrose, like Montrose, has wandered around on maps over the years. On Google Maps, Primrose is located at the junction of County Road A and Primrose Center Road, in the Town of Primrose. It’s at the intersection of sections 15, 16, 21 and 22 in Township 5N, Range 7E. (Fig. 22)

Today the junction is surrounded by large parcels of agricultural, forested and undeveloped land. There is one residential building on the northwest corner, but there are no services or businesses. (Fig. 31)

On historic Dane County maps, Primrose P.O. appears in the 1870s at the southwest corner of the junction. A school is on the northwest corner, where the residential building sits today. By 1890 the post office has moved a mile west (today the junction of County A and Norland Road). This location is used on maps through 1904, but by 1914, Primrose (with no P.O.) has moved back to the junction of County A and Primrose Center Road, where the post office stood on the 1870s. This is the location used on the 1939 WLEI map. (Fig. 32)

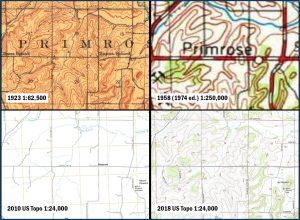

On USGS topographic maps, the name Primrose (the community, not the Town name) is missing from the 1923 1:62,500-scale map, but appears on the 1958 1:250,000-scale map, and reappears on maps of various scales up to and including the 2010 and 2013 editions of the US Topo maps. The name is absent from the 2016 and 2018 US Topos. The location of Primrose on all USGS maps is the eastern location, at the junction of County A and Primrose Center Road, close to the school and original post office location. (Fig. 33)

Cassidy observed the same inconsistencies, noting that after the closure of the Post Office, the community has been shown in different locations on different maps. He notes that at none of these locations is there a settlement still in existence.

Conclusion: Another example, like Montrose, of a map label affixed to a post office that had to find a new home when the post office was closed, and used a school to do so. There are no businesses or services here, or at the junction of County A and Norland Road a mile to the west.

Forward

Forward is located west of Primrose, on County Highway A between County Highways H and JG, in the Town of Perry. (Fig. 22)

Today Forward is surrounded by agricultural, forested and undeveloped land. The community itself is very small, with only a couple of remaining residential structures. (Fig. 34)

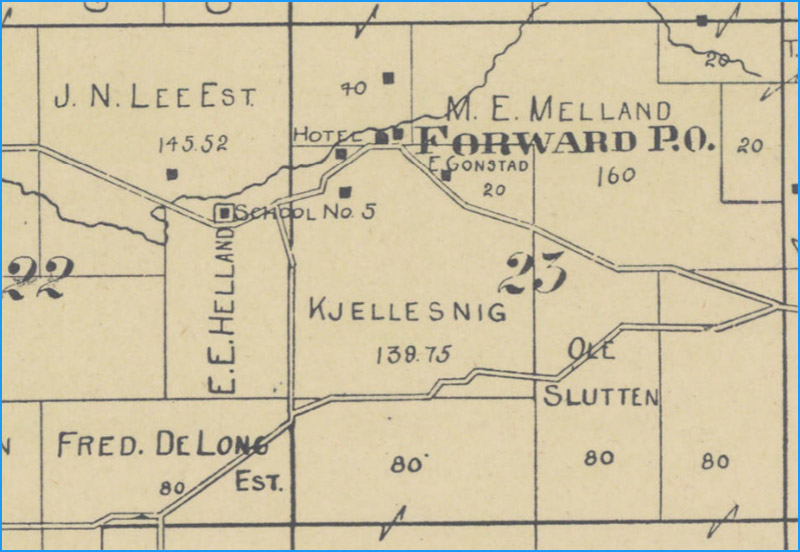

It may be small now, but in the past Forward was a busy place. Maps from the late 1800s show a post office, a hotel and other buildings. (Fig. 35)

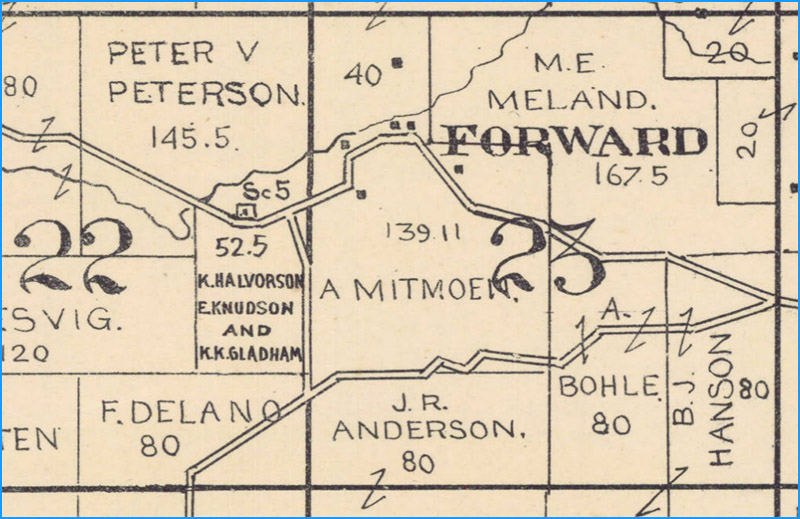

The P.O. disappears from the name by 1904, which agrees with Cassidy’s statement that the Forward Post Office was closed in 1902. (Fig. 36)

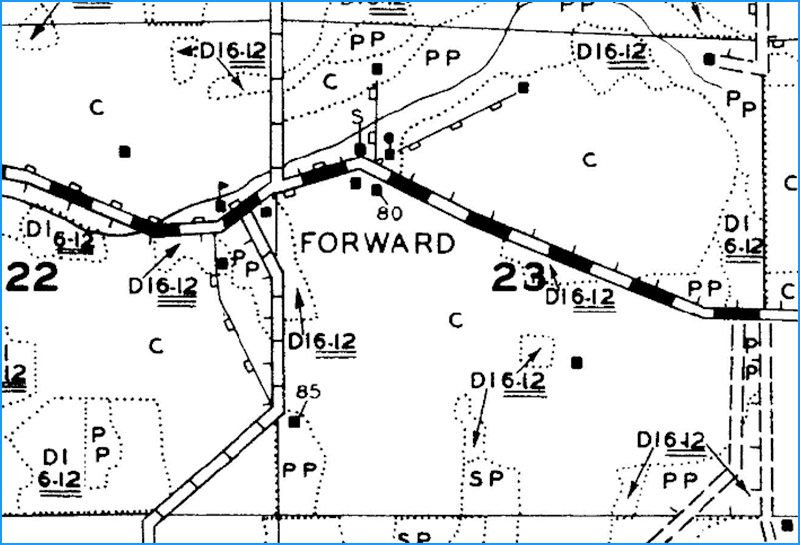

Forward continues to appear on maps well into the 1930s, including the 1939 WLEI map which shows the community with a few houses, a store and a gas station. (Fig. 37)

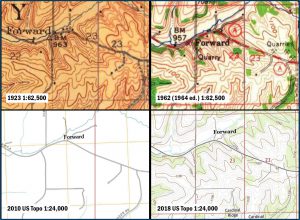

Forward appears on the first USGS maps of the area from 1923 (1:62,500-scale) and continues to be seen on later maps of various scales, including all four editions of the US Topo maps. (Fig. 38)

Conclusion: Forward was a small but locally important community and business center into at least the late 1930s. Unfortunately, there’s not much left today. If you need gas or coffee, you might need to consider Mount Horeb, ten miles to the north.

Vermont

Our tour is in its final stage, and we have moved into the northwest quadrant of Dane County. (Fig. 39)

Our first stop in this region is Vermont, which appears on Google Maps midway between Black Earth and Mount Horeb, on County Highway JJ approximately three-quarters of a mile east of the junction with County Highway J. The mapped location of Vermont is in the Town of Vermont, which can be confusing, since the Town of Vermont is real but the community of Vermont at this location is not.

Today, this location is surrounded by agricultural, forested and undeveloped land. There are no buildings of any kind close by. The closest building is Vermont Town Hall about three-quarters of a mile west on County Highway JJ. (Fig. 40)

The place name of Vermont was not found any any historic Dane County maps and atlases going back to the mid-1800s. (Fig. 41)

One of the few buildings consistently shown on these maps is a school, which is at the current location of the Town Hall. As the photograph of Vermont Town Hall (Fig. 40) shows, the school building appears to still exist.

The earliest USGS maps of this area from 1920 do not show a Vermont at this location. The name first appears on the first two editions of the US Topo maps (2010 and 2013) but then quickly disappears from the 2016 and 2018 editions. (Fig. 42)

Conclusion: While the Town of Vermont exists, it seems highly unlikely that a community named Vermont ever existed at this location. Most likely, the town name was inadvertently used as a map label on an early USGS map, perhaps due to the proximity of Vermont Town Hall, and the error persisted through later map editions. While there’s not much to see at Vermont, if you are passing through you can visit picturesque Elvers at the junction of County Highways J and JJ less than a mile to the west. Elvers was a vibrant community at one time with a saw mill, grist mill, post office and cheese factory. A few structures still remain. (Fig. 43)

Aldens Corners

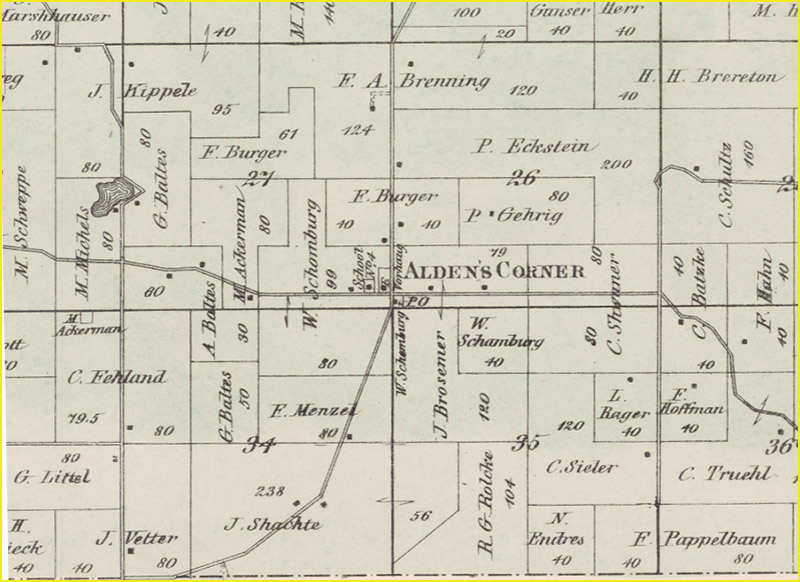

Our last stop is Aldens Corners. On Google Maps, Aldens Corners appears at the junction of US-12 and Breunig Road, about 6 miles southeast of Sauk City, in the Town of Roxbury. (Fig. 39)

Today this road junction is surrounded by large agricultural and forested parcels. There are two homes on the west side of Breunig Road north of US-12, set back from the highway by a frontage road (Old Highway 12). A photograph of the junction looking north across US-12 shows what the location looks like today. (Fig. 44)

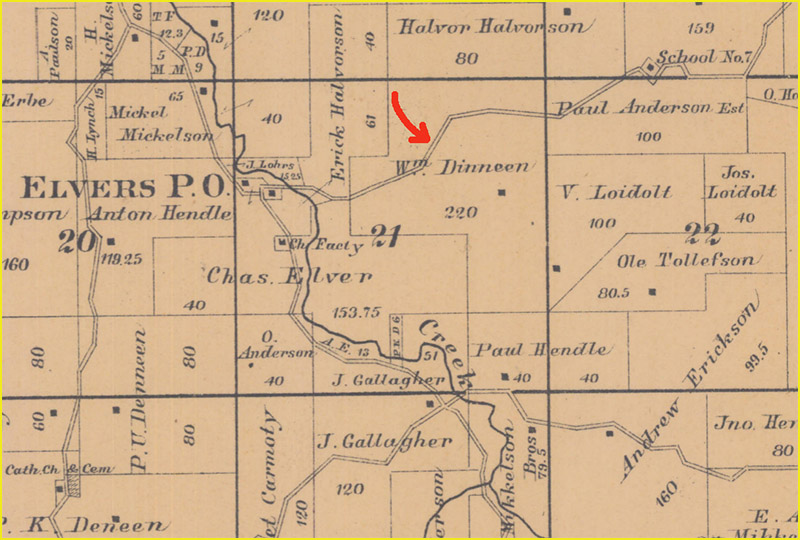

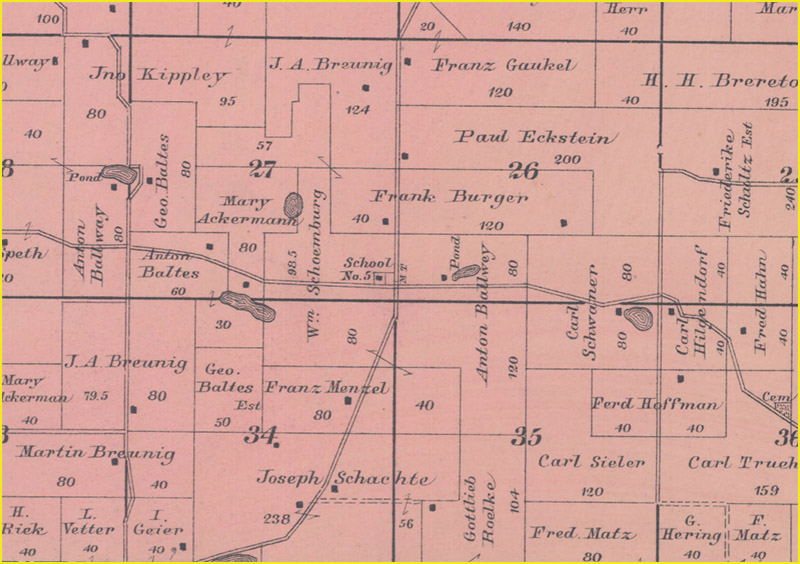

Aldens Corners was apparently recognized as a place as early as the 1860s, when a post office was in existence there. Maps from the 1870s show the name Alden’s Corner with a school, post office and a few other structures. (Fig. 45)

By 1890, the place name has disappeared along with the post office. The only building shown is the school (School No. 5). (Fig. 46)

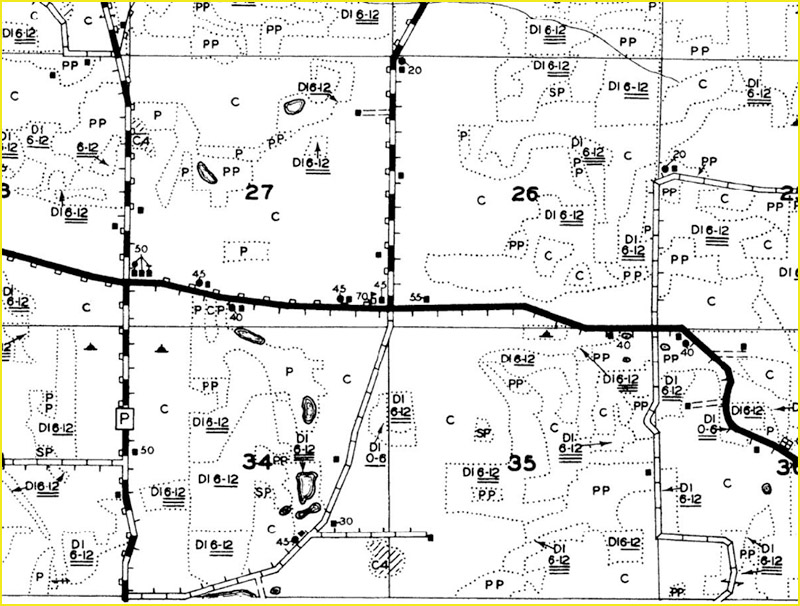

This agrees with Cassidy, who states that the post office closed in 1879 and that the name was no longer in use (p. 4). Aldens Corners was not found on any of the other Dane County plat or county maps, although the school continues to appear as the only building at the road junction. By 1939 the school is shown as vacant. (Fig. 47)

The earliest USGS maps from the early 1900s show a building and church at the road junction, but no community name. The name does not appear on later maps. Aldens Corners makes an appearance on the first two editions of the US Topo maps (2010 and 2013) but disappears from later editions. (Fig. 48)

Conclusion: Evidently a small community existed here until the late 1800s, but declined with the closure of the post office and later the school. Aldens Corners seems to have contained only a few buildings even when it was at its largest. Today you don’t even need to slow down to pass through Aldens Corners on US-12.

Parting Thoughts

I hope you have enjoyed this tour of these Dane County places, or at least found it educational. There are several points I’d like to make in parting.

My first point is the most obvious one: Maps cannot always be trusted. Remain skeptical. Just like the HAL 9000 computer in 2001: A Space Odyssey, maps are made by humans and are therefore prone to error.

Second, you may have noticed that many of the errors seen on Google Maps are also seen on USGS maps, and vice versa. This suggests a common link between the two maps. This link is most likely GNIS, the Geographic Names Information System, operated by the US Board on Geographic Names (BGN) and described as the “official repository of domestic geographic names data, the official vehicle for geographic names use by all departments of the Federal Government, and the source for applying geographic names to Federal electronic and printed products.” All of the places we visited on this tour are listed in GNIS as “populated places,” defined by the BGN as places or areas “with clustered or scattered buildings and a permanent human population (city, settlement, town, village). A populated place is usually not incorporated and by definition has no legal boundaries.”

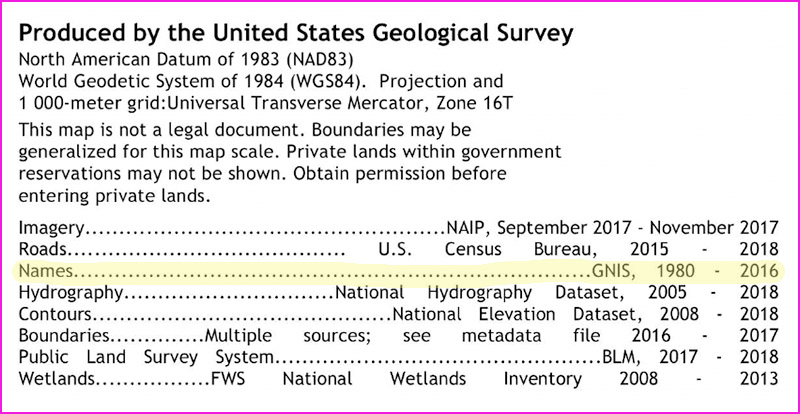

The USGS’s US Topo map program uses GNIS for place names, as shown in the marginalia of these maps. (Fig. 49)

The occurrence of GNIS place names on Google maps — especially unusual names like Buss’s Corners (which, unlike most possessive-form place names, actually contains an apostrophe) — strongly suggests that Google uses GNIS for place names too, including GNIS records with errors.

My third point is that looking at historic maps only takes us so far when it comes to verifying the existence of these rural communities. Just because Five Points, for example, does not show up on historic maps of Dane County does not necessarily mean that this name is not used locally as a reference point (as in, “We live a mile west of Five Points.”) The only way to get at that information is to survey the inhabitants of these areas and ask them. The results of such an exercise could be interesting and useful.

I have not said that much about why some of the places on our tour have essentially disappeared. However, one cartographic clue is the prominence given to post offices on historic maps. Taking Fig. 28 as an example, Montrose P.O. is by far the largest and most prominent label on the map, suggesting the importance of the rural post office as a community anchor. You may also have noticed how many post offices were closed around the turn of the 20th century, a development initiated by the advent of RFD (Rural Free Delivery), which provided mail delivery directly to rural residents’ homes rather than a post office. RFD was politically contentious in its day, and many local merchants feared that it would negatively impact local economies and businesses. The cartographic evidence certainly lends support to this idea, although without more research this is somewhat conjectural. Whatever the cause, however, historic maps clearly show that over the last 150 years what these rural communities have lost is their commercial function. Some homes may remain, but the gas stations, stores and hotels have essentially disappeared.

I hope this article proves that we need a more nuanced way to portray rural communities on maps. Small populated places that still have a visible footprint — like Forward and Hanerville — have a place on maps. However, it’s not appropriate to label these places using the same font size used for communities with hundreds or even thousands of people. Following standard cartographic practice, map-makers should assign population estimates or “importance codes” to these places, so that fonts can be sized appropriately. Places like Door Creek also fall into this category, although the map needs to reflect the current location of the community, not the historic one.

For historic places that no longer have a presence on the ground, and for places that never really existed as communities, a different map treatment is needed. Since these are not populated places, they should be pulled out into a separate map layer and rendered with a font and/or symbol that is distinct from that used for populated places. These places should display only at large map scales the same way points of interest do. Rather than wiping these historic places off the map, we should preserve them and acknowledge their uniqueness and historic value. If we can use maps in this way to get people to slow down, pull over and try to imagine the Wisconsin landscape as it once was, then it will be worth doing.

Special thanks to Taylor Ajamian and Melanie Kohls for their editorial suggestions. Map images are from the Wisconsin Historical Society online collection, UW-Madison Libraries (WLEI maps) and the US Geological Survey. All photographs are originals taken by the author.