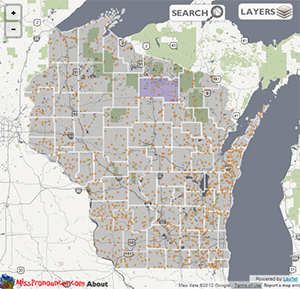

In mid-November, the State Cartographer’s Office (SCO) released a new online mapping application called Pronounce Wisconsin. Frequent visitors to our Web site may have noticed the new app in our list of online tools.

Pronounce Wisconsin is a pronouncing gazetteer of Wisconsin place names. A gazetteer is a list of places, often used in conjunction with a map or atlas; a pronouncing gazetteer also gives the pronunciation of each place name. Pronounce Wisconsin delivers audio pronunciations for over 1700 Wisconsin places, including counties, cities, villages, and unincorporated communities. By simply mousing over the map, users can immediately hear how the names of these places are pronounced.

MissPronouncer.com

Pronounce Wisconsin is a collaborative effort between the SCO and Jackie Johnson, creator of MissPronouncer.com. Jackie is a reporter and anchor at Wisconsin Radio Network, a radio news network that produces newscasts and stories for affiliated radio stations statewide. She created MissPronouncer.com over six years ago to help people correctly pronounce the names of places, elected officials, parks, famous people, and other phenomena specific to Wisconsin. MissPronouncer.com is a comprehensive, online pronouncing gazetteer for the state that simply required a map interface to make it fully geo-enabled. Pronounce Wisconsin links MissPronouncer.com’s digital audio archive to an interactive map interface to allow users to explore Wisconsin’s unique place names geographically.

Printed pronouncing gazetteers have long been a staple of map libraries worldwide, with authoritative versions produced by Lippincott, Rand McNally, and other map companies and geographical societies. But these publications require users to be familiar with pronunciation marks, pronunciation respelling systems, or phonetic alphabets in order to decipher the correct pronunciation for a place.

The advent of the Internet has allowed gazetteer databases to be accessed online. In the United States, the definitive example is the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) maintained by the US Geological Survey. GNIS is the official repository of place names in the U.S., having been developed to support the efforts of the U.S. Board on Geographic Names. The Getty Thesaurusis another example and includes place names (including preferred, variant, and historic names), place type, and position in the geographical hierarchy. While GNIS and TGN are both accessible online, pronunciations are not a feature of either database.

Quick Links

Place name pronunciations are also the subject of academic research, including some ground-breaking work at UW-Madison. Frederic G. Cassidy’s 1947 book “Dane County Place-Names” remains a valuable example of an effort to systematically capture place name etymology and pronunciations within a specific area, in this case Dane county, Wisconsin. Cassidy, a Professor of English at UW-Madison for many years, went on to become Chief Editor of DARE, the Dictionary of American Regional English. DARE has been active at UW-Madison for decades cataloging and compiling regional variations in pronunciations throughout the United States.

Another academic connection is the Center for the Study of Upper Midwest Cultures and the affiliated Wisconsin Englishes Project. These groups are studying the dialects of Wisconsin English speakers and have produced many interesting maps on this topic. These research efforts reflect the fact that there is not always a single correct pronunciation for a place; MissPronouncer.com is described by its creator as a “halfway decent” pronunciation guide for just this reason.

MissPronouncer.com is unique in that it makes use of Web technology to deliver pronunciations as audio content – sounds that can be heard by the user – based on modern audio file formats and the playback capabilities of Web browsers. While this technology has been around for some time, MissPronouncer.com is the first of its kind, providing online access to a comprehensive set of place name pronunciations for Wisconsin that users can actually hear. No understanding of arcane phonetic alphabets and codes is required – a huge benefit for English and non-English speakers alike.

The power of this approach is recognized within the geospatial community. For example, at a 2006 workshop on digital gazetteer research sponsored by the National Center for Geographic Information and Analysis (NCGIA), attendees noted that the use of audio files to deliver place name pronunciations is not being fully utilized, and that more research is needed to integrate pronunciations into gazetteer services.

One interesting parallel to MissPronouncer.com is Forvo, a Web site that purports to be the largest pronunciation guide in the world. Forvo allows users to capture, play back, and rate pronunciations crowdsourced from around the world in any language. While Forvo is not specifically a gazetteer, it does include some place names. For example, at last count Forvo had 15 pronunciations for Wisconsin, including one from a contributor in Australia, and one in French (“le Wisconsin”).

MissPronouncer.com’s ease of use helps explain the popularity of the site. Stories about MissPronouncer.com have been featured on numerous TV and radio stations, and in many online news sources, both regionally at a national level. Here’s an interesting example from WISN-Milwaukee showing how challenging Wisconsin place names can really be. Most recently, MissPronouncer.com was highlighted on MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow Show following Maddow’s embarrassing mispronunciation of a place name in Michigan. In 2007, Jackie Johnson received special commendation from Governor Jim Doyle for creating a Web site that helps people navigate the “quagmire of names of Native American and European descent for which Wisconsin is so well known.” These examples underscore the importance we ascribe to place names as a component of our cultural heritage and regional identity.

Origins of Pronounce Wisconsin

Pronounce Wisconsin actually began as an effort by the SCO to compile an authoritative map of Wisconsin’s unincorporated communities. This effort is part of the midscale mapping project the SCO launched in 2011 to develop a consistent set of statewide GIS-based cartographic layers.

An unincorporated community (or unincorporated place) is a concentration of people that is geographically not part of an incorporated city or village. Unincorporated places do not have legal boundaries or official governments. They are not recognized as political units, and do not have the powers that cities and villages have to tax, zone, or create local ordinances. Because of their unofficial status, they are also transitory features of the landscape, easily forgotten when populations dwindle, land use change occurs, or an area is annexed by an adjacent municipality.

Despite their nebulous character, unincorporated places are also quite real. Their names may appear on maps, on roadside signs, on restaurants or shops, and on letters delivered in the mail. They certainly exist in the mental maps of their inhabitants.

Unincorporated communities are not exactly the same as “towns” in Wisconsin, although there is some overlap. New England and Great Lakes states divide their counties into towns (or townships) that possess legal and administrative functions. In about half of these states, Wisconsin being one example, there is no overlap between municipal (city/village) and town governments. Nevertheless, confusion over names can easily occur. For example, the village of Deerfield (Dane county) is completely surrounded by the Town of Deerfield, and both place names have the same etymology. This type of situation is very common in Wisconsin, with numerous examples in many counties.

Or consider the unincorporated community of Taycheedah (Fond du Lac county), which is located within the town of Taycheedah. Not only do these places share the same name, but because Taycheedah is an unincorporated community, it is legally part of the town of Taycheedah. To complicate this problem, multiple unincorporated communities within a town may have similar names, such as Leeds, Leeds Center and North Leeds, all of which are in the town of Leeds (Columbia county).

Another difficulty with unincorporated places is that their status is not consistently tracked by any single agency. Only a handful of the largest unincorporated places are identified by the US Census Bureau, which refers to them as Census Designated Places, or CDPs. Because of the inherently ambiguous nature of unincorporated places, other attempts to enumerate them for Wisconsin have led to inconsistent results, with no real consensus about how many of them exist or exactly where they are located.

Over the past year, students and staff at the SCO compared available data sources to create an integrated unincorporated place dataset. Our sources included GNIS, the Wisconsin Department of Transportation county map series, a listing prepared by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, and hardcopy and online maps maintained by individual counties. The locations of unincorporated places were corrected using US Department of Agriculture NAIP imagery from 2010. The current dataset contains 1051 unincorporated places, all of which are displayed, with their pronunciations, in Pronounce Wisconsin.

This dataset represents the first phase of a longer data development effort. Having built an initial integrated view of Wisconsin’s unincorporated places, we are now in a position to work with others at the state and national level to make improvements to the dataset. Of particular importance here is GNIS, which presents a special challenge given its official role as a place name repository and its importance in the USGS’s current topographic mapping program.

The SCO’s interest in unincorporated places is to preserve information about these communities as a resource for citizens of the state. As such we are interested in your feedback, suggestions, and ideas. If you have information you would like to share, please use the Feedback/Contribute button on the Pronounce Wisconsin landing page or email me directly.

Building Pronounce Wisconsin

Like the SCO’s other online apps, Pronounce Wisconsin is built using open source software. The backend is comprised of a Postgres/PostGIS database, as well as static GeoJSON files, while the front end relies heavily on CSS and Javascript, including Leaflet.js, jQuery, and jQuery UI. jQuery is used primarily for map control interaction, and jQuery UI is used for the autocomplete search functionality.

Leaflet was chosen as the mapping framework because of its light weight, ease of use, native mobile compatibility, and strong development community. Google map tiles were chosen as the default basemap layer because of the ability to remove place names, helping to minimize confusion with our own place names for cities, villages, and unincorporated places. In addition, the Google map tiles were restyled using a more neutral color scheme more appropriate for a basemap. Google Satellite and Open Street Maps basemaps were added to provide users with options for visualizing the areas around unincorporated places.

Map features (unincorporated places, cities, villages, and counties) are loaded into the map frame from either a PostGIS database or from GeoJSON files depending on the zoom level. Testing revealed that static files give better performance at small (zoomed out) scales, while a database query performs better at large (zoomed in) scales.

Pronounce Wisconsin has a help page that provides simple directions for the user, including how to use the navigation tools, how to switch the basemap, and how to search for places. Known problems and limitations of Pronounce Wisconsin include an occasional (approximate 5 second) delay in loading features, and features loading more quickly than the basemap (in the case of Google tiles).

In addition, we do not recommend that users run the app using Internet Explorer version 8, due to a lack of support in this browser for application functionality. Maintaining backwards compatibility with older versions of browsers is always a challenge, and users are encouraged to upgrade to the newest browsers versions whenever possible. Our testing shows that Pronounce Wisconsin works with current versions of all major browsers including Explorer, Chrome, Firefox, and Safari. In addition, the app runs on mobile devices, although some behavior may not be optimal; for example, there is no ability to change the basemap on a mobile device. Please use the Feedback/Contribute button on the Pronounce Wisconsin landing page to report any issues you encounter.

Pronounce Wisconsin is an example of a project that has benefitted tremendously from student assistance and support. The SCO provides opportunities for University of Wisconsin-Madison students to gain practical experience with GIS and geospatial technology through applied service-learning projects. Data development for Pronounce Wisconsin, including many hours verifying unincorporated place names and locations, was provided by John Czaplewski, Scott Moucka, Erik Myers and Kim Ness, students in the GIS Certificate Program in the Geography Department at UW-Madison.

The interactive mapping application itself – including interface design and software development – was created by John Czaplewski as part of his internship project. AJ Wortley, Senior Outreach Specialist at the SCO, provided John with assistance through the project. At the SCO we feel fortunate to be able to support student work that not only yields practical benefits for the student, but also provides a valuable resource for the SCO’s community and the citizens of the state in general.